Timeline of African American Experience at UM: Pre-1950s

TIMELINE

pre-1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000

History of African-American Studies Program

Information provided by the University of Mississippi Libraries Archives and Special Collections

1848–1950

1848–1865

Notes from the Board of Trustee Minutes

The Proctor Report, 1859

State the hire of two servants (slaves), Marcus and Martin, for the year 1858 from B. W. Dacey and L. R. Mullins respectively.

Board of Trustee Minutes, 1850

“Contracts have been entered into by me as follows:

Paid A. G. Ellis for servant hire up to 6th February 1850 $83.25

Paid clothing for servant. $6.50

Amount of servant hire for two servants as per

contract for year 1850. $220.00

Proctors salary for 83 days from appointment

to l1th January 1849. $58.90

Proctors salary for half year from 11th January

to 11th July 1849. $125.00

Proctors salary from 11th July 1849 to 11th

July 1850. $250.00

$743.65”

Board of Trustee Minutes, 1848–1860

State the amount, two hundred and twenty dollars, for the hire of two servants and the amount of six dollars for the purchase of clothing for servants.

Resolved that the servants employed about the College, be under the control & direction of the Proctor and Faculty, and that they be required to devote all the time not necessarily engaged in cleaning up the dormitories, and furnishing the same with the necessary water, and making fires, to cleaning off the College grounds as the said Proctor & Faculty may direct, and that said servants are not allowed to leave the College grounds without permission of the Faculty, which was adopted.

University of Mississippi Catalogues of Officers, Alumni and Students, 1853-57

Policies concerning students bringing servants from home, or hiring servants while attending the university.

The Branham Affair*

The Branham controversy began in early May 1859 when the Barnards were in Vicksburg attending the Southern Commercial Convention. Barnard had gone to the convention at the request of James Howry to make peace with board member Isaac N. Davis. When the Barnards returned on May 17, Professor Boynton, who lived in the other wing of their faculty house, told Barnard that two students, J.P. Furniss and Samuel B. Humphreys, had entered his residence on the night of May 12 “with shameful designs” on one of his “defenceless female servants.” Jane, at twenty-nine the younger of the two servants, was apparently raped and in defending herself was badly beaten. Professor Boynton, after hearing a scuffle and loud noise, went outside to the fence separating the yards. He saw the two boys leave the residence and learned their identity from other students students several days later. Mrs. Barnard also told the chancellor that Jane had identified Humphreys as the assailant. Furniss was a bystander and not involved in the altercation.

The faculty summoned Humphreys to a called meeting on May 23. He pleaded not guilty to entering the chancellor’s residence and assaulting Jane. After taking testimony from several students, the faculty found Humphreys not guilty. Barnard, Boynton, and Moore voted guilty. Richardson, Carter, Phipps, Henry Whitemore (professor of Greek) , and Stearns voted not guilty. On a second vote, a majority of the faculty declared Humphrey “morally convicted” but did “not consider the evidence . . . sufficient, legally, to convict him.” under mississippi law, a slave could not testify against a white person in court. A majority of the faculty believed Jane’s identification of Humphreys was not admissible in the proceedings against him. Therefore, the faculty took no action against Humphreys.

After the faculty declined to expel Humphreys, Barnard wrote his parents and asked them to withdraw him from the university, which they did. When Humphreys reapplied for the fall session, Chancellor Barnard rejected his application. His refusal to allow Humphreys’s readmission spawned a small student rebellion and provided Branham a pretext with which to challenge Barnard’s soundness on the slavery and states’ rights. In protest of Barnard’s action several students withdrew from the university and transferred to Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee, but most of them returned the next year.

Branham, Carter, and Richardson soon began a “whispering campaign” against Barnard accusing him of dismissing a student on the basis of “negro testimony.” Professor Carter leaked the proceedings of the May 23 faculty meeting and insinuated that the faculty vote was sectional, the Northern men voting to convict and the Southern men voting not guilty. Stevenson printed every rumor and charge in the Mercury and denounced Barnard and the university’s other Northern-born professors. The rumors and accusations became so serious and so persistent that Barnard wrote to Governor John J. Pettus, ex officio chairman of the board of trustees, asking for “the fullest and most searching investigation” of the charges against him, especially the accusation that he was unsound on slavery. Governor Pettus called a special meeting of the board of trustees at Oxford for March 1, 1860. James Ventress hastily wrote to William Sharkey, urging him to attend the Oxford meeting to help him defend the chancellor.

For two days, March 1 and 2, the board heard the testimony of seventeen witness called by Branham and Barnard. The most influential of seventeen witnesses was Barnard himself. He testified that he had never discussed the assault with his slave, Jane, and that he had relied on evidence furnished by other sources to determine the guilt of Humphreys . Furthermore, he argued, because the governance of the university was parental, not municipal, the testimony of a slave, though he did not use it, was admissible and valid in the proceeding against a student. As to the question of slavery, Barnard declared, “I am as sound on the slavery question as any member of the board.” It was a convincing argument but not altogether a true statement. Barnard owned slaves, but he had misgivings about the institution and would soon renounce it.

Shortly after dark on the second day of tesimony, the board of trustees retired to its meeting room in the Lyceum. After considering the two days of testimony, the board unanimously absolved Chancellor Barnard of all the charges against him and ordered the proceedings, including its resolution clearing Barnard of all charges, printed and distributed throughout the state.

*Passage taken with permission from author, David G. Sansing. The University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History, University Press of Mississippi (1999) 96-98.

1865–1900

For the University position on the admittance of African Americans during Reconstruction see John Waddel, Memorials of Academic Life: Being a Historical Sketch of the Waddel Family (Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1891), p. 466-468.

1900–1940

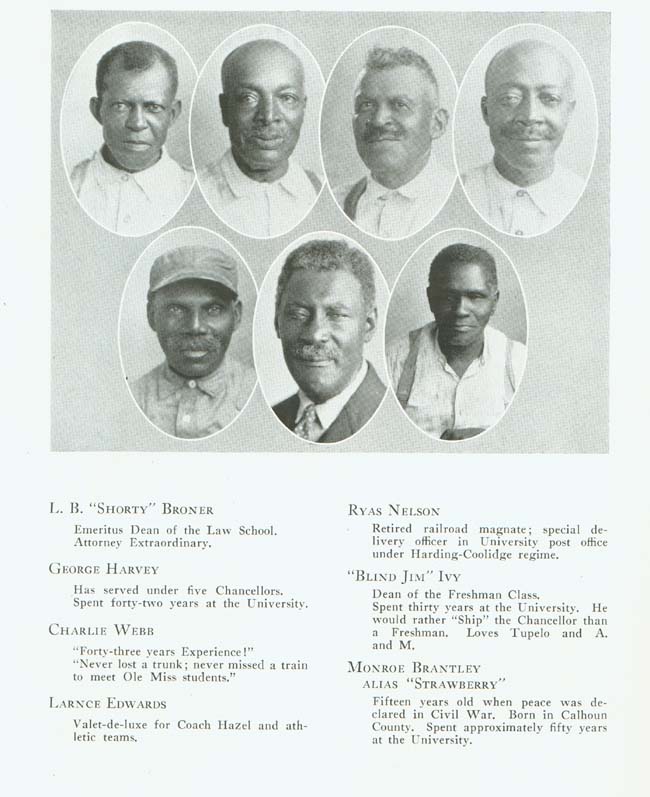

Early African American figures on campus:

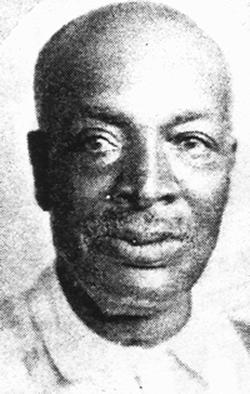

Blind Jim Ivy

Blind Jim Ivy became an integral part of the University of Mississippi in 1896. Ivy was born in 1870, and was the son of African slave Matilda Ivy. He moved from Alabama to Mississippi in 1890. Ivy was blinded in his early teens when coal tar paint got into his eyes while painting the Tallahatchie River Bridge. Ivy was considered the university’s mascot for many years. He was a member of Second Baptist Church and led efforts to rebuild the church roof.

George Harvey

Eliza Campbell Wilburn (slave name Wilbourne) became the first African American to serve as a cook when she worked for Chancellor George Frederick Holmes at the inception of the University.

After Eliza’s death, her daughter Emma followed her as a cook for the Chancellors. Her husband, George Harvey, worked as a handyman. They worked for four Chancellors from 1892 to 1932: Fulton 1892; Kincannon 1907-1914; Powers 1914-1924; Hume 1924-1930; and Powers again from 1930-1932. They lived in the Chancellor’s home which was located in Barnard Observatory on campus. Later they moved into a two room house erected for them on the premises. George and Emma Harvey passed away in the 1930’s and were commemorated by the University for their long service.

The Harvey family, for two more generations, continued to work for the University in the bookstore, dormitories, fraternity houses, sorority houses and mail service totaling more than 14 decades. Emma and George’s two sons, Ulysses and Bishop, worked in the bookstore, post office, and dormitories.

Information provided by Ms. Susie Marshall, Oxford Development Association, and the Harvey Family.

C. B. Webb

Clifton Bondurant Webb began work on the University of Mississippi campus at the age of thirteen during the 1910’s. He worked at the University for 56 years as a baker creating cakes and bread. Webb was active in a wide variety of community affairs. As a Board Member of the Oxford Development Association, Webb was interested in improving African American housing in Oxford at affordable rates. He was instrumental in providing public housing to the community. Today the C.B. Webb Townhouses located on 900 Molly Barr Road in Oxford, Mississippi, are named for him.

Information provided by the Oxford Development Association.

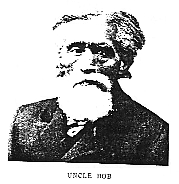

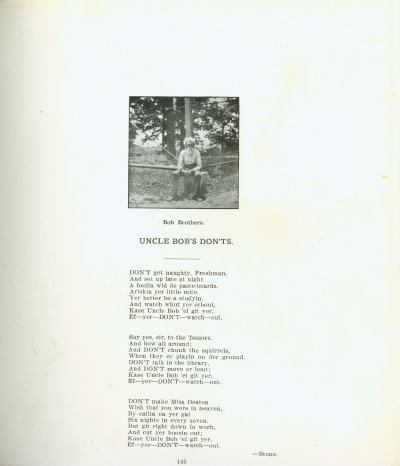

Uncle Bob Brothers

In 1913 the University of Mississippi yearbook remembered the passing of Bob Brothers.

“For 30 years a true and tried servant, a loyal instrument of our Alma Mater, now, all those who have been near and dear to him the long gone to Another Land, he is left alone, dried leaf, barely clinging to the bough that has held him. In all probability his place will be vacant when the first bell rings next year. God make his sunset days mellow and sweet with the kindness of those whom, in humble wise, he has helped to serve. God make the final wrenching loose of the leaf from the bough gentle and without pain, and find the good old darky a place of rest after long, long toil.”